In 1993, the Clinton administration launched an aggressive campaign to reduce the federal deficit, which had been hovering around 5% of GDP. Key policy steps included raising the top individual income tax rate from 31% to 39.6%, increasing the corporate tax rate to 35%, raising the federal gasoline tax by 4.3 cents per gallon, expanding the taxation of Social Security benefits, eliminating several tax deductions, and reducing defense spending from 4.3% to 2.9% of GDP. This last cut was often described as the “peace dividend” following the end of the Cold War.

The results were dramatic. By 1998, the U.S. achieved its first federal budget surplus since 1969, and by 2000 the surplus peaked at $236 billion. The economy was booming, driven by productivity gains and the tech boom, with average GDP growth near 4% during the late 1990s. President Clinton left office with an approval rating of approximately 65%, the highest of any postwar U.S. president.

But could such a strategy work today? The answer appears to be no - and for structural reasons.

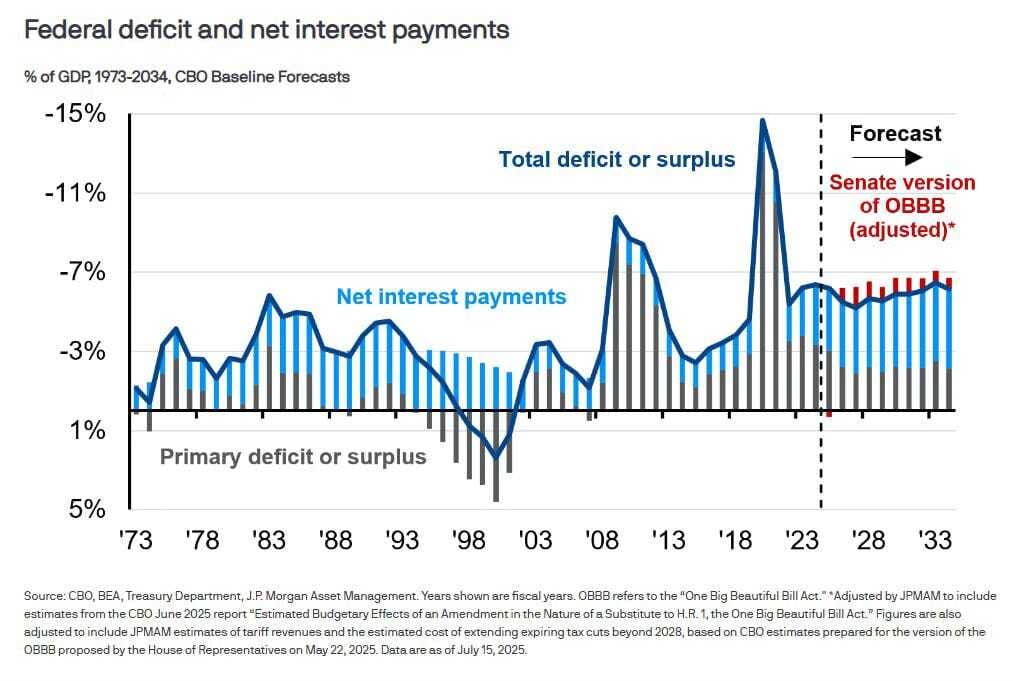

First, mandatory spending - Social Security, Medicare, and veterans’ benefits - now accounts for nearly two-thirds of the federal budget, up from under 50% in 1993. Second, while interest payments on the national debt still take up roughly 8% of the budget, the total debt has grown from $4.5 trillion in the early 1990s to more than $36 trillion today. Third, the population aged 65 and over has increased by more than 30%, adding sustained pressure to entitlement programs. And fourth, defense spending is once again rising due to renewed geopolitical tensions.

In late 2022, the Congressional Budget Office (CBO) proposed 84 potential measures to reduce the deficit - none of which involved cutting major entitlement programs. These included taxing carried interest as ordinary income, eliminating tax exemptions for new municipal bonds, and raising excise taxes on tobacco products. However, even if fully implemented, these steps would only reduce the deficit by an estimated $300 to $500 billion over 10 years. That’s a drop in the bucket, given that the federal deficit is currently running at over $1.5 trillion annually.

Tariff revenues introduced during the Trump administration do offer modest support to the federal budget, but those gains have been almost entirely offset by the continued extension of broad tax cuts.

In short, the U.S. deficit problem is now structural. With roughly 70% of the federal budget effectively locked in - either by statute or political reality - meaningful reductions through discretionary spending are all but impossible.

That leaves policymakers with one remaining lever: lowering interest rates and returning to monetary expansion. In other words, turn the printing press back on.